Benefits of an EHR - Practice Management Adoption

Dr. Robert Hoyt, health informatics expert, explains the need for electronic health records for practices and healthcare alike.

Practice Fusion - Benefit of switching to an EHR » Health Informatics: A Practical Guide – Page 4

Practice Management Integration

Most medical offices have had computerized practice management (PM) systems for many years, regardless of whether that office maintains paper medical records, electronic health records (EHRs) or a hybrid of these two. As will be pointed out, there are many reasons why PM systems have become so prevalent but one of the main reasons is for more rapid claims submission and adjudication. Without an electronic system, time and money would be lost on faxes, phone calls and snail mail. The American Medical Association estimated that inefficient claims submission systems lead to about $210 billion annually in unnecessary costs.91 A PM system is designed to capture all of the data from a patient encounter necessary to obtain reimbursement for the services provided. This data is then used to:

- Generate claims to seek reimbursement from healthcare payers

- Apply payments and denials

- Generate patient statements for any balance that is the patient’s responsibility

- Generate business correspondence

- Build databases for practice and referring physicians, payers, patient demographics and patient encounter transactions (i.e., date, diagnosis codes, procedure codes, amount charged, amount paid, date paid, billing messages, place and type of service codes, etc.)

Additionally, a PM system provides routine and ad hoc reports so that an administrator can analyze the trends for a given practice and implement performance improvement strategies based on the findings. For example, a medical office administrator is able to use the PM system to compare and contrast different payers with regards to the amount reimbursed for each given service or the turnaround time between claims submission and payment. The results lead to deciding which managed care plans the practice will participate in versus those plans that the practice may want to consider not accepting in the future. Another example is to analyze all payers for a given service performed in the practice to determine if that service is a good use of the practice’s clinical time. This analysis provides one aspect of whether or not the practice should consider continuing to offer a certain service such as case management of a patient who is receiving home health services through an agency. Of course, the administrator has to weigh services that aren’t profitable against any negative impact on overall patient satisfaction but the PM system provides a means of analyzing payment performance. Most PM systems also offer patient scheduling software that further increases the efficiency of the business aspects of a medical practice. Finally, some PM systems offer an encoder to assist the coder in selecting and sequencing the correct diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Current revision, clinically modified for use in the United States, or ICD-XX-CM) and procedure (Current Procedural Terminology, fourth edition or CPT-4® and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System or HCPCS) codes. Even when a physician determines the appropriate codes using a superbill, (a list of the common codes used in that practice along with the amount charged for each procedure), there are times when a diagnosis or procedure is not listed on the superbill and an encoder makes it efficient to do a search based on the main terms and select the best code. Furthermore, some encoders are packaged with tools such as a subscription to a newsletter published by the American Medical Association (AMA) known as “CPT® Assistant” that help the practice comply with correct coding initiatives which in turn optimize the reimbursement to which the practice is legally and ethically entitled and avoids fraud or abuse fines for improper coding.

Clinical and administrative workflow in a medical office

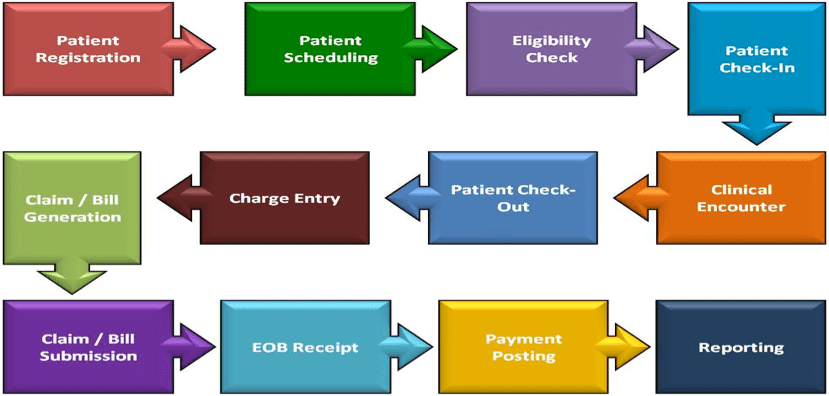

Several steps are common to almost any medical practice with regards to treating patients and getting reimbursed properly for the services provided. The steps are subdivided based on whether or not the patient has been to this practice previously for any type of service. The first step is to get the patient registered. This can be accomplished via a practice website or by the patient calling the office to schedule an appointment. Figure 4.5 demonstrates typical outpatient office workflow.

Figure 4.5 Typical outpatient office workflow

Patient registration.

This step includes obtaining demographic information, including any healthcare plan or plans the patient has and establishing which member of the patient’s household is financially responsible for any balances due either at the time of the visit or after claims adjudication by any healthcare payer(s) the practice agrees to bill for the patient.

Patient scheduling.

The patient is then scheduled for an appointment. If the patient had a previous encounter with the physician, the office receptionist simply has to update any changes to the patient information already on file.

Eligibility check.

For a new patient the insurance information must be verified to ensure that the patient is currently covered by a plan accepted by the practice and the planned services are a covered benefit. If not, the patient must be notified in advance of the visit to determine if they are willing to accept full financial responsibility for the services (i.e. full payment then attempt to get reimbursement from their healthcare plan on their own) or cancel the appointment and find a participating physician. If a practice offers web-based patient registration, there are some choices ranging from designing the website and all applicable online forms internally to contracting with a forms services company. Based on the amount of money the practice is willing to spend, a forms company offers basic forms design for use on the practice’s own website. Alternately, they can subcontract to use the company’s server and website for forms design, updating, processing and transmitting information to the practice’s EHR or PM system. See Medical Web Office services for a sample range of forms and communications services available for medical practices.92

Patient check-in.

The patient checks in for the scheduled visit. If already established with the practice the receptionist simply verifies/updates the patient information. If the patient is new, and the data gathered to schedule an appointment was obtained via telephone, the patient is asked to complete a registration form and provide a copy of his or her insurance card(s). Any information not previously obtained is keyed into the computer system for use by the PM system and the source document is added to the paper medical record, if applicable. Scanning the information is an option with an EHR. Most practices that have a PM system that is integrated with an EHR can scan the documents (including bubble sheets completed by the patient at time of registration) into the system once and the information is posted to the appropriate places in both the EHR and the PM system. Sometimes the data that is used by both the EHR and the PM software, such as patient name, is saved to a common database in an integrated system. At other times, however, the shared data is communicated electronically between the EHR and the PM system even though the databases are separate. It is important to know that when the systems have a shared database, this database only contains the part of the clinical record that is used to obtain reimbursement such as the patient demographics, diagnoses and procedures, dates of service, etc. However, the purely financial information is only found in the PM system – such as amount billed and amount paid or information about health plans. This is because it is not advisable to combine the business aspects of health information with clinical aspects. What procedure is done on a given date and the diagnosis that justifies the medical necessity of a procedure is both clinical and financial but how much the procedure costs and how much the patient paid out-of-pocket, etc., is purely financial.

Clinical encounter.

The patient is generally first seen by a nurse or medical assistant, to have vitals taken, collect blood and urine samples, if needed, and update the patient’s subjective history. The patient is then examined by the physician who takes additional history and completes the objective physical exam and updates the clinical notes in SOAP order – Subjective, Objective, Assessment and Plan. In a paper system, the physician dictates either during the visit or as soon afterward as possible and a transcriptionist creates a paper copy of the notes. Alternately, some physicians use voice recognition technology to dictate directly into a laptop or other device then print out the report generated by the software to file in the paper record. As discussed previously, in an EHR system clinicians have several options for inputting patient information into the clinical record. They can use voice recognition software, standard dictation or templates. Therefore, when the physician is face-to-face with the patient, the EHR would have already been started for that encounter by a nurse or other physician extender who would have entered the patient’s chief complaint, vital signs and possibly any updates to the patient’s subjective history (the subjective portion of the SOAP note). The physician will continue building the encounter notes by using a series of drop-down menus to indicate body systems examined, tests performed, tests or prescriptions ordered, (the objective portion of the SOAP note), the assessment and the plan. Each selection made by the physician adds to the clinical notes. Clinical notes are a good example of data that is maintained in the EHR but not shared with a PM system. However, EHRs that use computer assisted coding (CAC) technology can convert the standardized notes into codes and the codes are used by both the EHR and the PM system. For example, many EHRs can run the office notes through logic to assign CPT evaluation and management (E&M) codes based on either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines. The EHR system can pass these codes plus many ICD-XX-CM codes over to integrated (same vendor) or interfaced (different vendors) PM system when the systems are compatible. The physician concludes the clinical aspects of the encounter by giving the patient discharge/follow-up instructions and patient education literature. Any lab samples are sent to the lab and, if the patient needs a prescription and the practice uses e-prescribing, a prescription is sent from the EHR to the pharmacy electronically or via Fax. If not, the patient is given a paper copy of the prescription.

Patient check-out.

The patient is discharged after a receptionist collects any money due and schedules any follow-up visits. If the practice has chosen this feature, the EHR can interface with the PM system scheduler so the physician can schedule a follow-up visit and the patient can take home a printout of the office notes, any education material, the next appointment, plus a paper copy of physician orders or prescriptions for facilities not linked with the EHR.

Charge entry claims-bill generation.

In a standalone PM system, the charges are entered, often from a superbill but sometimes the services are coded from the information in the medical record. In an integrated PM with EHR system, the information needed is sent directly from the EHR to the PM system and a claim is built as described above. However, a person responsible for correct coding and billing must still verify that all applicable codes were brought over to the PM system, add any codes that the system did not assign automatically and scrub codes which means to link the diagnoses to the correct procedures that justify medical necessity and check for obvious errors in order to get them ready to submit as claims to payers.

Claims-bill submission.

The claims are sent electronically in all but rare cases but they are sent in cycles so once the PM system is updated, the claim is in queue waiting for transmission to a clearinghouse or directly to the payer, such as Medicare.

Remittance advice (RA) and explanation of benefits (EOB) receipt.

Once the claim is sent, the payer electronically (again, there are some exceptions in which the practice will actually get a paper check in the mail) sends a remittance advice (RA) containing the details for each charge paid or denied in that cycle. The RA contains an EOB (payments, denials, denial reason, reduced payments and reasons, patient responsibility, whether or not the claim was sent automatically to a secondary payer, etc.) for each charge by patient.

Payment posting.

The money is electronically deposited into the practice’s account. The payer generally mails a paper copy of each individual explanation of benefits to the patient. Billing personnel also have to follow-up when a person has more than one payer, to determine that the claim was transmitted to the appropriate secondary payer. If there is still a balance after the biller has applied payments and written off any charges in excess of the allowed amount for a particular payer, the system moves the balance into a queue to await patient billing. The biller is also responsible for tracking claims and initiating the collections process if a balance due by the patient is not paid in a timely fashion.

Reporting.

Daily reports are run and verified to ensure deposits match, all patients who were seen that day have charges in the system, etc. There are both routine reports (daily, weekly, monthly and end-of-year) and ad hoc reports used by the practice.

Electronic Health Record Adoption

Outpatient (Ambulatory) EHR adoption

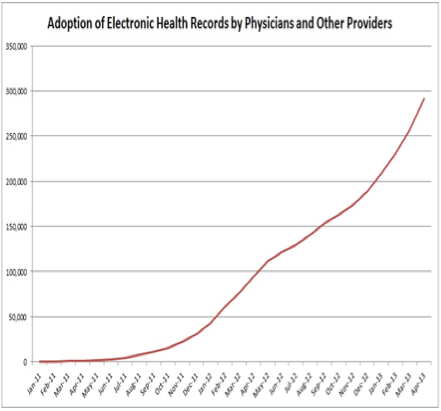

In 2006 the adoption rate of ambulatory EHRs was reported to be in the 10% to 20% range, depending on which study is read and what group was studied.93 Many of the commonly quoted statistics came from surveys, with their obvious shortcomings. It is also important to realize that many outpatient practices may have EHRs but continue to run dual paper and electronic systems or may use only part of the EHR. Furthermore, a significant concern is that small and/or rural practices are more likely to lack the finances and information technology support to purchase and implement EHRs. In 2008, a seminal article reported on the adoption rate of outpatient EHRs. In this study a sample of 5000 physicians was selected from the AMA master file but Osteopaths, residents and federal physicians were excluded. The most significant finding was that only 4% of respondents reported using a comprehensive EHR (order entry capability and decision support), whereas 13% reported using a basic EHR system. As has been reported before, the adoption rate was higher for large medical groups or medical centers. Responding physicians did report multiple beneficial effects of using EHRs.94 The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (2012) reported that 72% of office-based respondents had an EHR, compared to 48% reported in 2009. The percentage varied by state from a low of 54% to a high of 89%.95 Figure 4.6 shows HHS statistics for EHR adoption by physicians as of April 2013.96

Figure 4.6: EHR Adoption by physicians in the United States (Courtesy HHS Press Office

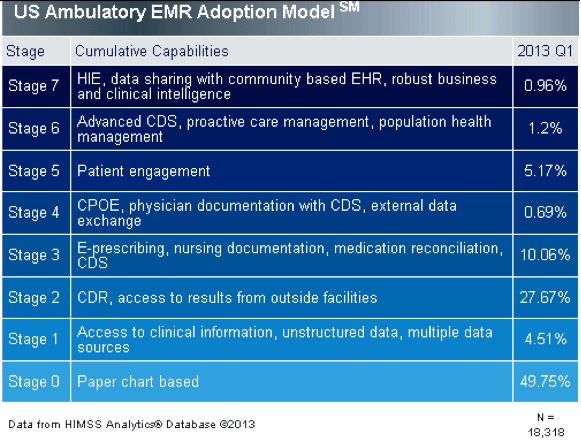

Adoption of an EHR does not necessarily indicate that the end-user is using the advanced capabilities of an EHR, as indicated in Figure 4.7 from HIMSS Analytics. HIMSS looked at data from over 5,000 US hospitals to determine the actual level of EHR adoption by stages of cumulative capabilities. In the first quarter of 2013, only 1.9% of hospitals surveyed had a complete EHR capable of CCD transactions, data warehousing and data continuity. The results indicate that very few hospital systems have achieved an advanced level of EHR sophistication.97

Figure 4.7: US Ambulatory EMR Adoption Model (Courtesy HIMSS Analytics)

Inpatient EHR adoption

In 2009 a study showed that 7.6% of the respondents reported a basic EHR system and only 1.5% reported a comprehensive EHR. Again, large urban and/or academic centers had the highest adoption rates. User satisfaction rates were not reported.98 The Office of the National Coordinator reported on EHR adoption to meet meaningful use and noted that as of 2012 there was a lot of progress. Specifically, of 24 meaningful use objectives examined, 16 had adoption rates of at least 80%.99 As anticipated, EHR adoption by rural or small non-teaching hospitals continues to be lower than by larger, urban hospitals and academic medical centers.100

International EHR adoption

Until recently, the US lagged behind many other developed countries in its adoption of EHRs. In fact, a 2006 study indicated the US were as much as a dozen years behind other industrialized countries in HIT adoption.101 A 2009 study showed that the US continued to lag in EHR adoption among primary care physicians in developed countries.102 A 2012 survey of the same countries demonstrated increases in the United States, from 46 to 69 percent and an increase in Canada from 37 to 56 percent. However, many of the EHR systems were basic so that the percent adoption of “multi-functional” EHRs is considerably lower, particularly in small medical practices.103 A major difference between the US and these high EHR adopter countries has been, until recently, the degree of government involvement. Other countries’ governments invested heavily in HIT. The United Kingdom, with 20% of the population of the US, committed $17 billion through its National Program for IT (NPfIT). Australia has provided subsidies to adopting physicians and has the National E-Health Transition Authority (NEHTA). Germany has a public-private partnership involved in promoting interoperability standards and certifying EHRs called Gematik. Denmark, long thought to be the international leader in health IT, has a very high EHR adoption rate and the most interoperable system of any country.104 All is not wonderful in other countries however. In 2011 UK officials announced that they planned to dismantle their $17 billion health IT project. They stated that some of the nearly $10 billion that they had invested to date was wasted and that their main vendor, Computer Sciences Corporation would not be able to provide the software that was promised.105 The HITECH Act of 2009, which created the EHR Incentives Programs in the US, is helping the United States catch up, which will be discussed further in another section.

Over 112,000 health care professionals use Practice Fusion for their EHR

See for yourself why our EHR was ranked #1 for ease of use.